Photographs are strange things. They speak to you on two registers, as Roland Barthes is wont to say in Camera Lucida (1980). Firstly, the studium. This is when the image communicates knowledge or information. The viewer demonstrates a kind of ‘enthusiastic commitment’ to obtain an idea of what is in front of him/her.

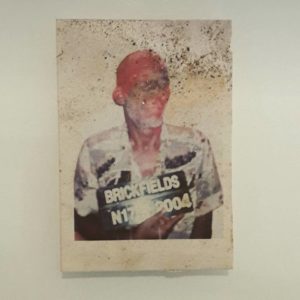

Take some of these portraits of criminals and policemen. These were found on the grounds of the police station in Brickfields and today belong to photographer Eiffel Chong. They were scattered and left behind when the station was shuttered up and moved somewhere else. These are portait photographs of two opposing forces of the law that we are socialised into believing since many of us began playing our childhood chasing game, police and thief. The good and the bad. The nice and the naughty. The one with power and the one who escapes from power.

But photographs also speak to us as punctum, which roughly translates to a kind of wounding, a bruise or a prick. It is a cut that reaches into our heart as we linger and study them closely. Suddenly an aspect of the photograph will leap out at you. Because of the innate quality of the photograph, it indexes a ‘that-has-been’ and a certain feature of the image will be calling out to you, asking you to dwell just a little longer. That’s when one realises that all things must pass. The punctum becomes a reminder of our own mortality.

‘What I can name cannot really prick me’ says Barthes. Perhaps what they ultimately represent is not so much the institution of police and its counterpart, the thief. These are things that can be named. When found, the photographs were all scattered on the ground, unseparated, all mixed up. The very logic of the institution has lost all sense of purpose as heat and humidity ate into a place, at the heart of our city, abandoned to time. Entropy has set in. It is a slow and gradual slide, not into disorder, but meaninglessness.

Arkib Stories by Simon Soon.