Competing Visibilities (Part 2): Visibility as Power – Mascot, Logo, and Installation

By Tan Zi Hao, 2013

To make oneself apparent is to demonstrate one’s prospect of power. Even a suggestive appearance of power is greater than its real but usually unrealised capacity.

It is Debord’s spectacle substituting realism, “that which appears is good, that which is good appears”;[1] or to paraphrase, “that which is visible is powerful, that which is powerful is visible”.

In the age of visual primacy, being big and visible is being powerful.

Photo credit: mauhorng.com

The new Democratic Action Party’s (DAP) inflatable “Water Ubah” now afloat in Penang is an example par excellence of a spectacularised politics. Its gigantism recalls DAP’s benchmark victory in the 13th General Election, but victory per se no longer suffices, one needs to exhibit and celebrate victory, to appear victorious. Produced with a budget of RM60,000, the mascot inflatable is a megalomania, a symbol that appears to defy what it is: inflated but empty; a representation of DAP’s political support base but in the pretense of representing the whole Malaysia (as claimed by Penang chief minister Lim Guan Eng);[2] a less generous simulation of Hofman’s Rubber Duck but a dissimulation of a hornbill which never actually swims.

Visibility has become the artifice of power. And Malaysia is not unfamiliar with this tactical exploit. When the fourth prime minister Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad vowed to put Malaysia onto the world map, his key was visibility.[3] Kuala Lumpur Tower and Petronas Twin Towers are phallic structures with an internationalist appeal calling for worldwide attention. One could even consider Mahathirism an epoch that centralises the spectacle, since not only is Mahathir a monumentalist with highly visible projects, he is a man of “vision”, a leader who privileges the sight, literally, with his “Look East Policy” and “Vision 2020”. Along with this came the Malaysia Book of Records initiative in 1998, where Mahathirism penetrated the mentality of every members of the society, further instilling an obsession towards monumentalism[4] and has since inspired succeeding macrophilic pursuits until today.[5]

The logo of International Islamic University Malaysia made of 19,300 doughnuts has set a record in Malaysia recently. Photo credit: facebook.com/Hiburan.My

All the recognitions are quantitatively founded, whose scale are determined by the frequency of repetition. “Malaysia Boleh!” (Malaysia Can!) then serves as the Mahathirist clarion call for unthinkable scales, igniting a capitalist engine within the postcolonial spirit. With mechanical reproduction comes prolificacy and efficiency.

Production is power, repetition constitutes scale. Relooking at the campaign period of the 13th General Election, similar strategies were deployed – the repetition of flags, logos, and mascots bombarded the sight of the public. While this was not new, the degree of repetition in this election was unprecedented: the amount of Barisan Nasional (BN) flags in Penang made into the headlines; 1Malaysia advertisements televised at every commercial break; non-stop personal letters and flyers from the prime minister’s office (read: BN); and even the previously discussed Malaysian Spring, despite being more variegated, utilised a similar strategy of repetition.

Repetition improves visibility.

Photo credit: spark-the-change.com

Repetition is also embraced by DAP’s “Ubah” online, and like Malaysian Spring, variation takes place. Each Ubah can be marked with different colours, in different positions and costumes, against different backgrounds. Altogether they multiplied into a plethora of choice made available as avatars. Unlike Malaysian Spring, however, the applicability of the mascot is restricted by its caricatured form. Whereas different parties can easily adopt Malaysian Spring’s visual tactic, Ubah is complicated in form, thus its potential for customisation and duplication is reduced. Only in rare cases did netizens take pain to modify the outlook, as was demonstrated by BN supporters who have appropriated Ubah in their cyber campaign.

DAP’s mascot hijacked by opponents.

Photo credit: Hee Woi Woon

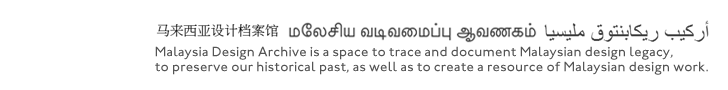

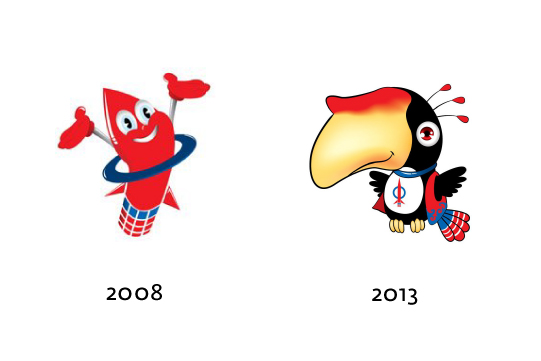

It is relevant here to say a few more words about DAP’s Ubah. The hornbill is only a fortuitous choice. Ubah was originally conceived for the Sarawak state election in 2011 by designer Ooi Leng Hang – a hornbill in Gayak traditional dress was deemed appropriate for Sarawak. Due to positive response, the presence of the hornbill was subsequently expanded nationwide, with the party committees later deciding to replace DAP’s initial mascot Rocket Kid (2008) with the hornbill Ubah (2013) in the 13th General Election.

From a rocket to a bird: Ubah has generated so much hype to the extent that DAP would surrender their rocket.

Photo credit: dapjelutong.blogspot.com (left); Ooi Leng Hang (right)

This re-territorialising of the hornbill as a geographical referent from Sarawak to Peninsula and the accidental reshaping of political identity of DAP is a commendable graphic intervention. Firstly, Ubah’s visibility is largely driven by the general public;[6] secondly, it is an unusual occasion of which Malaysian cultural influence travels westward; thirdly, its popularity moves from level of culture to affect the political party (by garnering support) and in consequence the political system.

The preliminary sketches of Ubah from the designer Ooi Leng Hang.

Photo credit: Ooi Leng Hang

DAP’s arch-opponent Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA; a subsidiary of BN) did not concede defeat and introduced a panda as their new election mascot, alluding to the prime minister’s continued good diplomatic relationship with China.[7] The emphasis given by each party mascot immediately suggests a different strategy of visibility: DAP’s hornbill is local, subaltern and indigenous, whereas MCA’s panda is a symbol of Asian brotherhood with a hint of global Chinese unity. The former is popular and has become repetitive with slight variation. The latter has not thrived online but remains faithful in competing for a quantitative advantage, most apparently with the doubling of the Chinese word “稳” (stability) in the naming of the panda “稳稳” (Wen Wen). It also speaks to DAP president Chua Soi Lek’s fondness of numbers, boasting of the almost 40 years of diplomatic ties with China,[8] the 1,000 Wen Wen snapped within minutes before the launch,[9] and the 20,000 Wen Wen expected to sell out or to be given away in Penang.[10] Here, quantity is a fulfillment that operates through seduction, and repetition is a fetish of power, an accomplishment in production and regeneration techniques. Both of which enhance visibility, even if the numbers are inaccurate opportunist estimates.

MCA’s election mascot “Wen Wen”.

Photo credit: malaysiakini.com

Unlike the opposition party, the ruling party BN has its way of repeating its brand without being unduly dependent on the internet. For example, during the launch of BN’s manifesto in April, BN politicians were found to be wearing a newly introduced blue shirt comprising countless of BN’s white scale, as if clamouring for visibility.

Barisan Nasional’s blue shirts filled with white scales are attention grabbing.

Photo credit: themalaysianinsider.com

The distinct logo of 1Malaysia has also become a proxy for BN’s logo towards approaching the election. Visible in the abbreviations of the many state-funded initiatives, the recurrence substantiates BN’s political commitment: BB1M (Buku Baucer 1Malaysia), BR1M (Bantuan Rakyat 1Malaysia), KIR1M (Kedai Ikan Rakyat 1Malaysia), KR1M (Kedai Rakyat 1Malaysia), MR1M (Menu Rakyat 1Malaysia), PR1MA (Perumahan Rakyat 1Malaysia), to name a few. Transforming the vowel into a number in the abbreviations suggests quantity over quality, a one-off fiesta envisioned by short-termed money politics. The elimination of the “I” also signifies an objectification of the self, where subjective experience and difference is erased: from “I” to “1”, “subject” to “object”, “wo/men” to “numbers”, “rakyat” to “voters”.[11] And BN’s neoliberalist aptitude for numbers and quantity proved advantageous during the election. Their victory derived from winning seats instead of popular votes serves as a constant reminder of BN having an upper hand in any quantitative game.

While opposition parties publicise themselves with the conventionally repetitive party flags, repetition comes at a less overwhelming rate due to lesser funds. At times, they appear more innovative in its appearance, especially in the rural areas. Party flags and banners were found enveloping different installations that represented a political scandal identifiable with the person involved: ring (Rosmah Mansor), handbag (Rosmah Mansor), ghost (Altantuya), cow (Shahrizat Abdul Jalil), submarine (Scorpene, and Najib Razak), and ear (Adnan Yaakob). These are narrative devices that vilify the political profiles without direct mention. Aside from symbolic objects, combatant vehicles such as tanks, jets, and helicopters were constructed by both ruling and opposition parties. What remains consistent is that this trend is mainly a rural occurrence, which indicates the proliferation of grassroots creativity and innovation in places with economic limitations.

Handbag from PAS (top-left); submarine from PAS (top-right); ship from BN (bottom-left); handbag from PAS (bottom-right).

Photo credit: kiflimally.com (top-left); securemalaysia.blogspot.com (all others)

PAS logo painted on mangos (left) and banana leaves (right).

Photo credit: source unknown

The minimalist look also attracts playful subversion. In response to BN’s new fancy blue shirt aforementioned, netizens have come up with a PAS version of the shirt: a green dress with white polka dots (as PAS’ full moons). The repetition of PAS’ logo is often accompanied by co-option and appropriation, and it is precisely this postmodernist innovation that elevates PAS’ collateral design (official or otherwise) into a whole new level during the 13th General Election.

Competing politics, competing fashions.

Photo credit: Lew Pik-Svonn (left); themalaysianinsider.com (right)

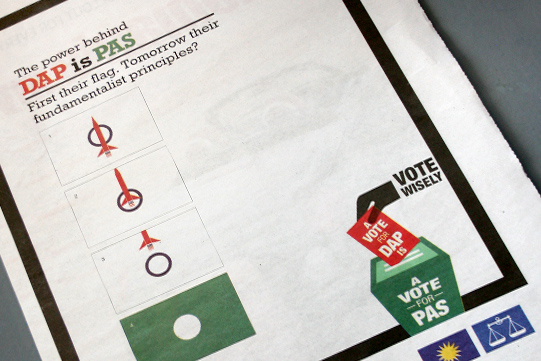

Another notable event is the visual warfare caused by the disqualification of the opposition DAP. A few weeks before the election, the Registrar of Society (RoS) renounced DAP’s central committee, rendering DAP illegitimate for the election. This compelled DAP to contest under a PAS logo in Peninsula and under a Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) logo in East Malaysia. MCA, who usually equates DAP with the Islamic PAS to raise fear amongst Chinese voters with the apparent threat of Islamisation immediately capitalised on this issue and published what appeared to be one of the most memorable, if not also controversial, series of political advertisements. One of the visuals alludes to a political deception and treachery: DAP transforms into PAS, DAP is PAS; the rocket takes off and the moon is all that is left. “A vote for DAP is a vote for PAS”.

The title reads: “The power behind DAP is PAS. First their flag. Tomorrow their fundamentalist principles?” Followed by “Who says DAP is good for you? Vote for Najib’s economic transformation. Vote for stability and prosperity;” “Vote wisely: A vote for DAP is a vote for PAS.”

Advertisement from The Star newspaper. Photo credit: Tan Zi Hao

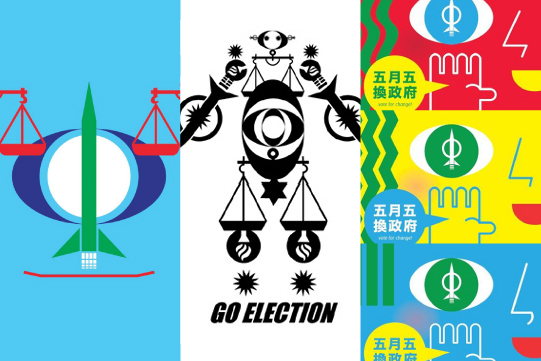

DAP’s counter-propaganda strategy turned out to be yet another clever visual manipulation: the rocket took off but landed on the moon (read: PAS). This visualisation immediately took the party supporters by storm. From political speeches to social media, the imagery of DAP’s rocket landing on PAS’ moon spread like wild fire. The momentum of the election, along with the supporters’ disappointment over RoS’ last-minute announcement and MCA’s attack ad, strengthened the relationship between PAS and DAP. The mainly Chinese DAP members and supporters even dedicated Teresa Teng’s classic “月亮代表我的心” (The Moon Represents My Heart) to PAS, as a sentimental way to promote PAS to the Chinese voters – all of which invariably feed into PAS’ recent branding: “PAS for all.”

Unlike repetition and scale, both MCA and DAP have employed a strategy of deconstruction and hybridity where graphics are dissected and reassembled, creating an assemblage [12] and approximating new forms of visibility. They are transgressive, risky, and chaotic, but aspiring. Although rarely practised in the mainstream, many creative practitioners have already been stretching the limits of political tolerance with more playful jumbles, as shown below.

Assemblages such as these can potentially capture the imagination of the audience and test the limits of political tolerance.

Design credit: Jun Kit (left); Grass Studio (middle); Driv Loo (right)

The battle is visual and each strives for more intense visibility. Since the “launching” of DAP’s rocket – ironically kick started by MCA – the political landscape has since turned surreal where spectators are gorged with signs and are indulged in the cinematics of power.

Power, a visual effect in politics today, can be contrived through repetition and scale, or through assemblage. Mahathirism introduced to us the former, desperate politics introduced to us the latter, and oppositional politics acquainted us with more organic visual methodology for increased variations where voices matter, not numbers. Amid competing visibilities, Malaysia’s visual culture evolves, inviting more creative actors to add onto the existing vocabulary. The question is this: does our visual activism take a form that reflects and corroborates our politics? If the answer is no, how are we convincing? If yes, how do we then navigate our politics to a reform still unheard of through politically unthinkable visuals?

===

Endnotes:

[1] Another relevant aphorism of Debord: “In the spectacle, one part of the world represents itself to the world and is superior to it.” Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (Detroit: Black & Red, 1983), para. 12, 29.

[2] Lim Kit Siang, “Launch on ‘Water Ubah’ in Penang in keeping with Malaysian Dream to have a united nation where Malaysians regard themselves as one people despite diversity of race, religion, culture and region,” Lim Kit Siang for Malaysia (July 2013), http://blog.limkitsiang.com/2013/07/13/launch-on-water-ubah-in-penang-in-keeping-with-malaysian-dream-to-have-a-united-nation-where-malaysians-regard-themselves-as-one-people-despite-diversity-of-race-religion-culture-a/ [accessed 20 July 2013]; Vickson Tan, “Penang DAP UBAH Di Air,” Only Penang (July 2013), http://www.onlypenang.com/events-in-penang/penang-dap-ubah-di-air/ [accessed 20 July 2013].

[3] Mahathir’s flamboyance is displayed through the architecture of his time. See R.S. Milne and Diane K. Mauzy, Malaysian Politics under Mahathir (London and New York: Routledge, 1999), pp.67–68; Mohamad Tajuddin Mohamad Rasi, Malaysian Architecture: Crisis Within (Kuala Lumpur: Utusan Publications, 2005), pp. 48–49.

[4] Stated outright at the beginning of a BBC’s report in 2003: “The BBC’s Jonathan Kent explains why the small country of Malaysia is so keen on beating world records, even those involving the world’s longest buffet.” Jonathan Kent, “Malaysia’s record-breaking obsession,” BBC News (February 2003), http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/2793415.stm [accessed 23 July 2013].

[5] Recently, Malaysia has the largest flashmob, the biggest logo ever made of doughnuts, and the longest stretch of tortilla wraps. See Diana Yeoh, “Gangnam-Style flash mob sets new record,” New Straits Times (February 2013), http://www.nst.com.my/streets/northern/gangnam-style-flash-mob-sets-new-record-1.212421 [accessed 23 July 2013]; New Straits Times, “UIAM gets into Malaysian Book of Records with logo made of 19,300 doughnuts,” New Straits Times (April 2013), http://www.nst.com.my/latest/uiam-gets-into-malaysian-book-of-records-with-logo-made-of-19-300-doughnuts-1.255238 [accessed 23 July 2013]; Christina Low, “Participants create 1,306 wraps to enter the Malaysia Book of Records,” The Star Online (June 2013), , http://www.thestar.com.my/News/Community/2013/06/15/Its-a-wrap-Participants-create-1306-wraps-to-enter-the-Malaysia-Book-of-Records.aspx [accessed 23 July 2013].

[6] Similar to Bersih’s choice on yellow. See Part 1.

[7] According to MCA’s president Datuk Seri Chua Soi Lek: “The reason why we chose a Panda is simple, it is to show that our prime minister has worked hard to foster good relations with China and we are one of their most important trade partners…Unlike (Opposition Leader) Anwar Ibrahim, who is only interested in the United States, Israel and the middle east. Let’s not talk about (PAS president) Hadi Awang who only knows about the middle east.” Nigel Aw, “Soi Lek: PM says plenty more time before GE13,” Malaysiakini (April 2013), http://www.malaysiakini.com/news/225631 [accessed 23 July 2013].

[8] The Star Online, “GE13: Move over hornbill, MCA’s panda is the people’s choice,” The Star Online (April 2013), http://www.thestar.com.my/News/Nation/2013/03/26/GE13-Move-over-hornbill-MCAs-panda-is-the-peoples-choice.aspx [accessed 25 July 2013].

[9] The Star Online, Ibid.

[10] The Star Online, “GE13: 20,000 soft panda toys to boost MCA’s campaign in Penang,” The Star Online (April 2013), http://www.thestar.com.my/News/Nation/2013/04/06/GE13-20000-soft-panda-toys-to-boost-MCAs-campaign-in-Penang.aspx [accessed 25 July 2012].

[11] Activist Pang Khee Teik wittily notes: “A country where every ‘I’ has been replaced by ‘1’ = a country w1thout 1nd1v1duals, just numbers, like pr1soners”.

[12] It is more useful to think of the word “assemblage” from the work of Deleuze and Guattari: “An assemblage is precisely this increase in the dimensions of a multiplicity that necessarily changes in nature as it expands its connections.” The divergence and convergence, deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation of different signs and metaphors activate productive relationships – a chain reaction. See Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), p. 8.

[end]